Introducción al estado de flujo

El estado de flujo, o "flow", es una experiencia psicológica especial en la que la persona se sumerge por completo en lo que está haciendo. En ese momento siente una oleada de energía, una implicación total y un auténtico placer. El psicólogo húngaro-estadounidense Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (1934–2021), creador de esta teoría, lo llamó "una fusión fluida entre acción y conciencia". En este estado, el tiempo parece distorsionarse, la persona se olvida de sí misma y el control de la situación se percibe como algo natural y sin esfuerzo.En su libro "Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience" (1990), Csíkszentmihályi explica que el flujo aparece en actividades con objetivos claros, retroalimentación inmediata y un equilibrio ideal entre desafío (la dificultad de la tarea) y habilidades (las capacidades de la persona). Imagina que estás tan absorto que te olvidas de la comida o del sueño. Precisamente esto es lo que hace que los juegos sean "adictivos": los diseñadores equilibran magistralmente la dificultad para que el jugador no se aburra (cuando la tarea es demasiado fácil) ni se ponga nervioso (cuando es demasiado difícil). En este artículo analizaremos la teoría de Csíkszentmihályi, veremos cómo funciona en los niveles de Super Mario y Dark Souls –juegos clásicos de los géneros de plataformas y "soulslike"– y entenderemos por qué este equilibrio mantiene la atención de los jugadores durante horas.

Para hacerlo más interesante, imaginemos que estás jugando a tu juego favorito y, de repente, las horas han pasado sin que te des cuenta. ¡Eso es el flujo! Ahora vamos a ver cómo crean esta magia los diseñadores.

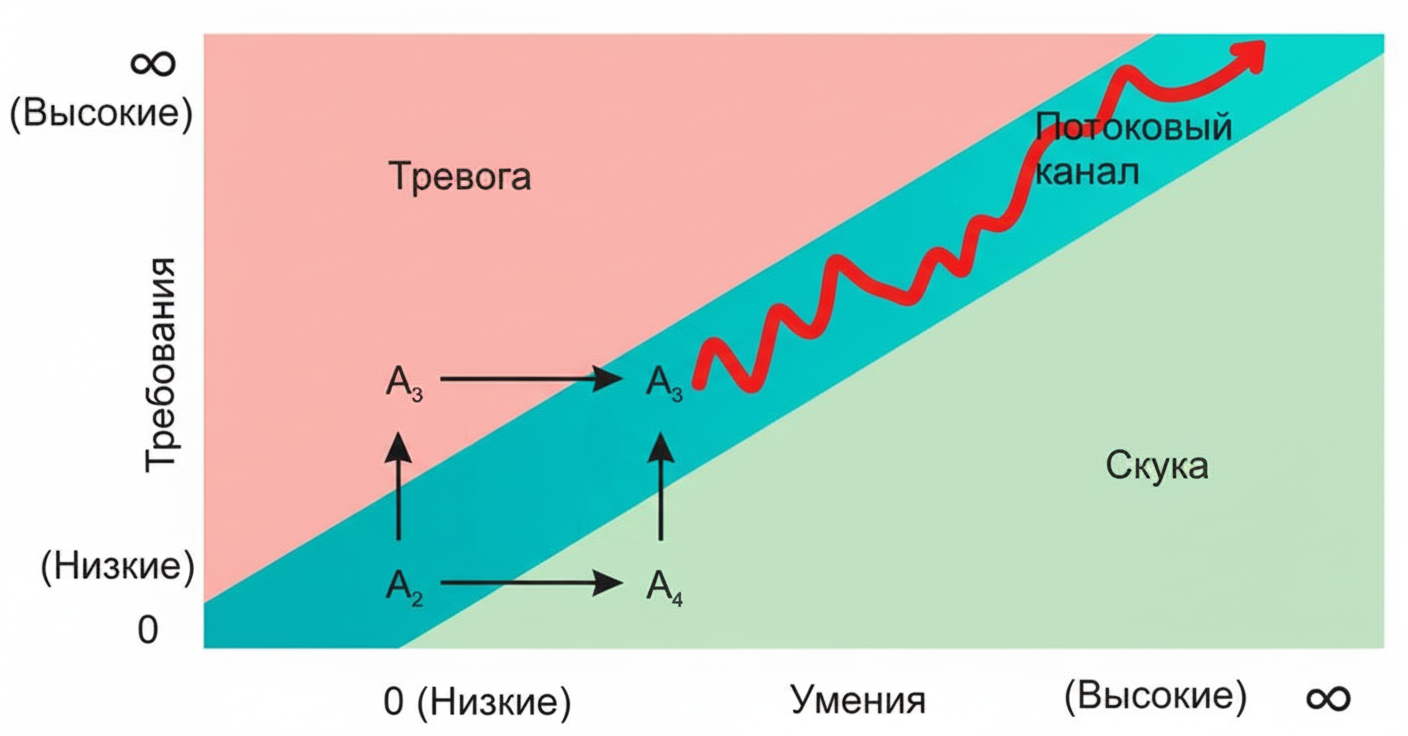

Teoría de Csíkszentmihályi: equilibrio entre desafío y habilidades

Csíkszentmihályi señaló tres condiciones principales para el flujo:- objetivos claros y progreso visible;

- retroalimentación inmediata (ves el resultado de tus acciones al instante);

- equilibrio entre desafío y habilidades, donde la tarea es un poco más difícil de lo que ya sabes hacer; esto te obliga a crecer y desarrollarte. Si el desafío es demasiado débil, aparece el aburrimiento; si es demasiado fuerte, surgen el estrés y la irritación.

- concentración intensa;

- fusión entre acción y pensamiento;

- pérdida de la sensación de uno mismo;

- sensación de control;

- distorsión del tiempo;

- recompensa intrínseca (placer del propio proceso);

- objetivos claros;

- retroalimentación inmediata;

- equilibrio entre desafío y habilidades.

Aquí tienes una tabla sencilla para que se entienda mejor:

| Estado | Habilidades en comparación con el desafío | Emoción | Ejemplo en juegos |

| Flujo | Equilibrio (el desafío es aproximadamente igual a las habilidades, pero un poco mayor) | Inmersión total | Superar el primer nivel en Super Mario |

| Aburrimiento | Las habilidades superan al desafío | Aburrimiento | Recolección repetida de recursos al final del juego |

| Ansiedad | El desafío supera a las habilidades | Irritación | Primer jefe en Dark Souls sin entrenamiento previo |

| Excitación | El desafío es igual a las habilidades (ambos bajos) | Excitación nerviosa | Nivel de tutorial para principiantes |

Esta tabla muestra por qué los diseñadores de juegos se esfuerzan tanto por alcanzar el "canal de flujo". Imagínalo en la vida real: si estás aprendiendo a montar en bicicleta, un camino demasiado fácil aburre y una bajada muy inclinada asusta. Lo ideal es cuando la ruta te hace esforzarte, pero no te hunde.

Para hacerlo más ameno, recordemos una historia: Csíkszentmihályi estudiaba a artistas, músicos y deportistas. Un pintor contaba que en estado de flujo se olvida del tiempo y de la comida, y se disuelve por completo en la creación. En los juegos ocurre lo mismo: te "pierdes" en el mundo virtual.

Flujo en el diseño de juegos: de la teoría a la práctica

En su trabajo "Flow in Games" (2005), Jenova Chen adaptó la teoría a los videojuegos. Considera que los juegos deben ampliar la "zona de flujo", ofreciendo distintos niveles de dificultad para novatos y expertos, desde jugadores casual hasta hardcore. La clave es el ajuste dinámico de la dificultad: no automático (cuando el juego cambia los parámetros a tus espaldas), sino activo, donde el jugador elige el nivel a través de las mecánicas del juego. Por ejemplo, en Tetris la velocidad aumenta poco a poco, obligándote a adaptarte; en flOw (creado por Chen) evolucionas eligiendo la "comida", y los niveles se ajustan de forma natural.Shigeru Miyamoto (creador de Super Mario) e Hidetaka Miyazaki (autor de Dark Souls) aplican esto de formas distintas: en Mario hay una progresión suave y lineal, como en un buen libro; en Souls el dominio se construye a través de los fracasos, como en la vida real, donde las lecciones llegan a través de los errores. Analicemos estos enfoques con más detalle, añadiendo ejemplos reales de juegos y datos curiosos.

Por ejemplo, ¿sabías que Tetris fue creado por el programador soviético Alexéi Pázhitnov? Probablemente ya hayas visto la película de 2023 y lo sepas. Su sencillez es un flujo perfecto: los bloques caen cada vez más rápido, tus habilidades crecen y te quedas "en la zona" durante horas.

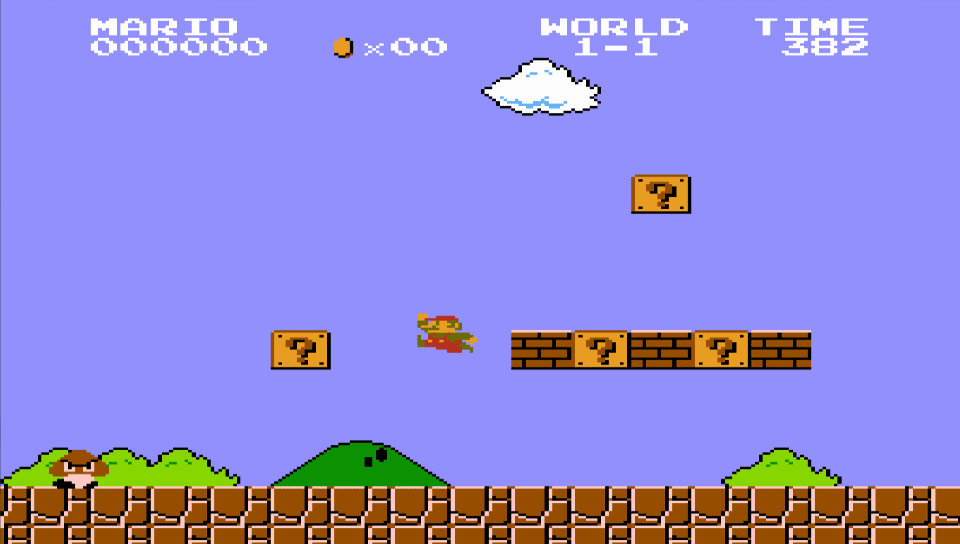

Super Mario: progresión suave del flujo

Super Mario Bros. (1985) es una auténtica obra maestra del equilibrio. El primer nivel (1-1) enseña lo básico: correr hacia la derecha (limitado por el mando), saltar sobre enemigos sencillos, un bloque con un signo de interrogación del que cae una seta de poder. El desafío aumenta gradualmente: primero plataformas fáciles, luego precipicios y bolas de fuego. Los puntos de control en medio del nivel permiten reiniciar sin volver al principio, devolviéndote a una zona de confort para recuperar la confianza.

En Super Mario Bros. 3, los niveles están construidos como "lecciones": el primer mundo enseña a saltar, el segundo a nadar, el tercero a volar. Este enfoque mantiene al 80–90% de los jugadores en flujo y reduce el abandono. Un dato curioso: Miyamoto se inspiró en recuerdos de su infancia en la naturaleza: saltar sobre setas como si fueran árboles. Esto convierte el juego no solo en entretenimiento, sino en una aventura en la que cada nivel es un nuevo capítulo de un cuento.

Imagina a un principiante que cae en un precipicio. En lugar de enfadarse, vuelve a intentarlo porque el nivel es corto y no da miedo perder. Para los veteranos hay secretos: niveles ocultos que añaden dificultad.

Dark Souls: flujo a través de la muerte y el dominio

Dark Souls (2011) es un flujo extremo para los amantes de la dificultad. Miyazaki crea un "flujo obstinado": te lanzas contra un jefe, mueres, estudias sus ataques, vuelves y lo derrotas, y entonces llega la euforia del triunfo. Las hogueras son puntos de reaparición, y las almas son experiencia y moneda que se pierden al morir, lo que te motiva a regresar para recuperarlas.

La retroalimentación es perfecta: los efectos visuales y los sonidos avisan de los ataques, y la pantalla de muerte muestra la causa. El ciclo "muerte–lección–reintento" eleva tus habilidades. Igual que en el modelo de Chen, se trata de un ajuste activo: eliges tu estilo de combate, ya sea espada, magia o escudo.

Un dato curioso: Miyazaki se inspiró en juegos de rol japoneses y en fantasía oscura como "Berserk". Los jugadores comparten historias del tipo: "Luché contra este jefe 50 veces, pero cuando lo vencí fue el punto máximo de felicidad". Esto transforma la frustración en motivación y convierte el flujo en algo "obstinado", pero muy gratificante.

Comparación de enfoques: Mario frente a Souls

Comparemos ambos enfoques en una tabla para verlo más claro:| Aspecto | Super Mario | Dark Souls |

| Progresión | Lineal, suave, como un manual | No lineal, depende del jugador, como en la vida real |

| Puntos de control | En mitad de los niveles, con bonificaciones | Hogueras, con riesgo de perder las almas |

| Retroalimentación | Inmediata: muerte o éxito | Inmediata: muerte o éxito |

| Flujo para quién | Para todos, con una baja barrera de entrada | Para entusiastas, con un techo alto de maestría |

| Retención | Reinicios cortos para evitar la rabia | Largo entrenamiento con un triunfo al final |

En Mario, los niveles son coloridos y la música motiva; en Souls, el mundo es sombrío y cada victoria es una hazaña personal. Esto demuestra cómo el flujo se adapta al género.

Retención de la atención: por qué el flujo funciona tan bien

El flujo mantiene la atención al máximo: en este estado, los jugadores ignoran las distracciones y el tiempo vuela. Las investigaciones confirman que el flujo está relacionado con la implicación: los jugadores vuelven por "un nivel más". En Mario, las setas de vidas extra motivan a explorar los niveles, y en Souls el modo "Nueva partida +" aumenta el interés de los veteranos al hacer que todo sea más difícil.Ambos enfoques utilizan la recompensa intrínseca: no solo premios, sino sensación de dominio. Juegos modernos como Elden Ring (de Miyazaki) o Celeste combinan dificultad adaptable y puntos de control. El resultado son horas de juego sin fatiga para el jugador.